Professor Latorre continued the research on his own dime after the government project ended and when Keith Barron had met him in 1998, Dr. Barron was extremely excited about two places: Sevilla del Oro and Logroño de los Caballeros. Dr. Barron returned to Ecuador in July 2000 and met with Prof. Latorre, who convinced him to initiate exploration. When Keith Barron went back to Ecuador in January 2001 to commence the programme it was after two months spent in library research at the USGS in Reston, Virginia, and the GSC in Ottawa. Initially, the field visits focused on the provinces of El Oro, Loja and Zamora-Chinchipe, all of which had legacies of gold production. When intensely altered breccias were found in outcrop near Alto Machinaza in the Cordillera del Condor, the whole project took a left turn and the company Aurelian Resources was born.

For the next five years the focus was on exploration, discovery and drilling numerous gold and copper discoveries on the Aurelian concessions, as well as making significant additions to the land package so that it was eventually circa 93,000 hectares. The Fruta del Norte gold discovery was made in March 2006, and thence all Aurelian’s work centred on developing the gold-silver resource there until the company was acquired by Kinross in November, 2008.

The accounts of the conquests of the Aztecs in Mexico by Hernan Cortez (1521) and the Inca in Peru by Francisco Pizarro (1532) are very well known. The subsequent systematic looting of fabulous gold and silver treasures, mostly in the form of ceremonial objects taken by force from the indigenous peoples or through grave robbing is almost certainly the greatest act of cultural piracy the world has seen since perhaps the sacking of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 AD.

Stories of the source of the Inca gold evolved into the mythology of El Dorado, which has fuelled many adventures into the interior of the South American continent, some of which were earnest exploration efforts but many of which were scams, which annoyingly persist even up to the present day. The reality is that the Inca and other indigenous peoples in the pre-Columbian era, mined gold and silver over at least 1,000 years from hundreds of source areas in South America; stretching from Colombia, through Ecuador and Peru to Venezuela, Guyana and Surinam. No single mine was responsible for the wealth of the Inca and it is a certainty that the Inca themselves took gold from subjugated peoples.

As the Conquistadors streamed into the interior of South America in the search for plunder, they encountered numerous active or abandoned gold mines, or virgin gold-bearing hardrock and placer occurrences. These were regularized into encomiendas or “mine camps” by the Council of the Indies, title of which would be awarded to a nobleman or in rare cases to a noblewoman, who as well as mining gold and dutifully yielding up the Quinto royalty or “King’s fifth”, were charged with indoctrinating the native population into the Catholic faith. Far from being benign patrons, the owners ran what were in essence, forced labour camps. Most encomiendas lasted a few years only, until the gold was depleted or the labour force killed off by Old World diseases such as smallpox and influenza for which the natives had no immunity. In the Spanish possessions of the New World, it was illegal to possess undeclared gold dust or nuggets. All gold production had to be surrendered to the Caja Real (the Royal Treasury) where it was cast into rough ingots bearing imprinted fineness, tax stamps and origin. A very few of these ingots have been recovered from modern salvage of Colonial shipwrecks, but typically they were not preserved and were recast into milled coinage when they reached Spain.

What has miraculously survived however are the voluminous written accountancy records, annual reports and other correspondence, most of which is housed in the Archive of the Indies, (Archivo General de Indias) in Seville, Spain, which is registered with UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. http://www.mecd.gob.es/cultura-mecd/areas-cultura/archivos/mc/archivos/agi/portada.html This is the main repository for documents from the Spanish Colonial era, by decree of Carlos III in 1785. More than 100 documents relating to Logroño de los Caballeros and Sevilla del Oro were located by professional archivists Guadalupe Fernández Morente and Esther González Pérez in Seville for Dr. Barron. The documents are all handwritten and were transcribed by them into text. They consist primarily of testimonials, ledger accounts of gold production from the Royal Treasury, court documents, reports to the Crown, or requests for honours, land, pensions, and titles. In the following text, references to unpublished documents from this archive are denoted “AGI”. These investigations were supplemented by personal archival searches (by Barron and/or Latorre) in various libraries in Ecuador, the Archivo Historico Arzobispal, Lima, the Riva Agüero Institute, Lima, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid, the Rare Book Section of the New York Public Library, the British Museum Library, and the Manuscript Section of the Apostolic Library of the Vatican.

After the civil wars in the Viceroyalty of Peru, La Gasca in 1548 divided the eastern governorates into four: Quijos, Macas, Yaguarzongo and Bracamoros. All new expeditions of exploration had to be pre-approved by the Council of the Indies in Spain. The Viceroy, the Marquis of Cañete gave the Conquistador Juan Salinas Loyola a commission authorizing him to establish encomiendas in every town he populated in Yaguarzongo and Bracamoros, from which he would profit after the King’s Fifth was deducted (Stirling, 1938). This lucrative arrangement was the impetus for the founding of the settlements of Loyola, Valladolid, Zamora, Santiago de los Montañas and Santa Maria de las Nievas in the period 1556 through 1559. In 1560, he founded Santa Maria del Rosario, which later became Sevilla del Oro. The founding of Logroño may have been by Salinas Loyola or by his nephew Bernardo Loyola, possibly as early as 1568. In 1569-1570 Salinas Loyola travelled to Spain to have his merits and rights as “Adelantado” recognized by the Council of the Indies. This would give Salinas Loyola the ability to be appointed Governor. He took gifts (gold samples) for the King.

“Logroño de los Caballeros” (or “Logroño of the Knights”) was named after the town of Logroño in the province of Rioja in Spain, near where Juan de Salinas was born. It was founded by the Knights Templar, hence its name. The Loyola family became fabulously rich through gold mining and refurbished a convent in the town to be funded “in perpetuity”. It fell into ruin in the 20th century but its baroque façade was preserved and the building now serves as the Parliament for Rioja Province (Martin, 2008).

Writing to the Council of the Indies in 1577:

“After my return (from Spain) I have been occupied in providing ruling and foundation to the four cities I left settled before I went to these realms……and have settled two others again in more convenient regions, that one is called Logroño and the other the New Sevilla de Oro, in all of these there are gold discoveries and every day there are more samples that promise more wealth…”

(AGI, Quito, 21, N.46).

Writing from the encomienda of Alonso Velasquez Gavilanes (1579):

“It has been over 6 years since you were in these parts and provinces of Peru…in the peace making of the locals of the provinces of Chapico and the rest of the regions, when following my order, Captain Jose Villamar Maldonado, came to settle in these same provinces the city of Sevilla de Oro, where you stayed for over two years….after which, having I (Santiago Loyola) come into such city of Sevilla de Oro we found it….giving the order to General Bernardo Loyola to go with a force to the provinces of the Jivaro to settle a city in the name of His Majesty and bring the locals to peace….you had joined him on his expedition to the aforementioned provinces and helped bring peace to those natives, until you were all obliged to settling in those provinces the city of Logroño, where you stayed as well over 3 years….”

(AGI, Council 126, R.14, April 19, 1582).

And by Juan Alderete, Salinas’ successor as Governor (and brother-in-law) (AGI, Patronato 294, No. 19):

In the city of Valladolid the 1st day of the month of December, 1582.

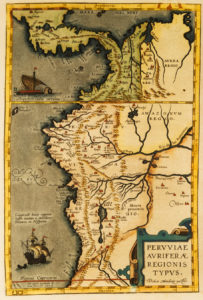

Dr. Latorre was aware of a very historically important map, in the world’s first atlas, by the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) labelled “Peruviae Auriferae Regionis Typus “ (Gold Regions of Peru) http://sites.fhi.duke.edu/defininglines/india/peruuiae/. This map clearly marks the settlements of Logroño and Sevilla del Oro, however due to its extreme age (1574) it can only be considered as an approximation. It predates the invention of the means to fix longitude, and so east-west measurements were by dead reckoning. Gold camp maps such as this were popularized after the beginning of the 1849 California Gold Rush, and 1898 Klondike Gold Rush and no doubt this map was produced and labelled such for similar reasons. This map is by “Didaco Mendezio”; the Latinized name for the priest/cartographer Diego Mendez. Dr. Latorre recognized early in this research that the Amazon basin on the map is clearly fantasy, and that the coastlines of South and Central America were more or less accurate but could have been taken from the Chronicle of Perú (1553), by the Conquistador and historian Pedro Cieza de Leon (Raul Porras, 1963) as well as other unpublished sources. What was intriguing was the relatively accurate positioning of the towns in the interior of what is now Ecuador. Dr. Latorre commented that this could only have been drafted by someone who had been “on the spot” or in dialogue with someone with first-hand knowledge of the area. This was echoed by museum curator Cecilia Bakula (2014).

Close inspection of the map indicates a place name called “El Pongo”. This is the famous El Pongo de Manseriche, which is a narrow gorge through which the Marañon River passes. It is a treacherous rapid. Salinas de Loyola descended the rapid in 1557. He testified:

“they came to two very dangerous rivers, and the paths ended, and there I populated the towns of Santiago (…). Later with some of the soldiers I navigated down the river in canoes travelling through narrow and dangerous rapids, especially the part the Indians call Pongo.” (AGI Patronage 113, R.7. Merits and Services: Juan de Salinas, Perú, Lima, Cuzco, 1565).

Mendez ended his days as Chaplain of the Monastery of Encarnation in Lima. Dr. Latorre found a document bearing his signature in the Lima Archives. Mendez is also mentioned in the Compendium by Vazquez de Espinosa.

In 2011, Dr. Latorre and Dr. Barron visited Rome. Dr. Latorre’s brother is Ecuadorian Ambassador to the Holy See and obtained permission to research in the Vatican Library. The trip was fruitless, with the exception of an excerpted transcription published in a 1950’s anthology (“Great Works in Spanish Literature”) of the “Compendium and Description of the West Indies”, by Fray Antonio Vazquez de Espinosa, of 1628-1629.

Unfortunately, the entire “backstory” to this famous and important document was omitted. Only when a full translation became available on-line in 2015 was it recognized that the original document resided in the Manuscript Section of the Apostolic Library of the Vatican (Barb Lat. 3584), in a different part of the library than where Dr. Latorre had been. The story of the re-discovery of this presumed lost document in the Vatican in 1929 by Charles Upson Clark of the Smithsonian Institution is fascinating and is fully discussed in volume 102, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 1942. A transcription in Spanish was published in 1948 by the Smithsonian.

Dr. Barron personally examined the 1629 document in May, 2016 and confirmed that the translation is accurate and complete. Photographic reproductions supplied by the Vatican are below.

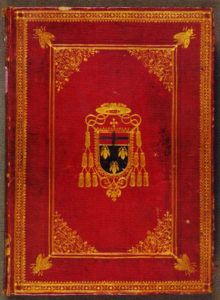

The Vazquez volume in finely gold-tooled Moroccan red leather binding, showing the Coat of Arms of the Barberini Family (and the Barberini bees).

Vázquez de Espinosa was a Carmelite priest who lived in the New World from 1608-1622, in Mexico, Central and South America and the Caribbean. He returned to his native Spain and wrote his Compendium and managed to get only a small part of it typeset before he died in 1630. The document chronicles his travels in the Spanish territories and provides a fascinating account of geography, botany, ethnology, anthropology, and ecclesiastical matters in the New World. He was in the Audiencia de Quito (present day Ecuador) in 1614 and baptized 3,000 natives (San Pedro Muñoz, 1948). The following are excerpts from the 1942 translation:

- 1111. Of the City of Sevilla del Oro in the Province of Macas.

Thirty leagues from this town [Riobamba] to the SE. is the city of Sevilla del Oro in the Province of Macas; it is mountainous country, and after crossing the Cordillera to get to this city, there is a paramo called Sufia (which means cold sierra) on which there are two very large lakes. Of the rivers issuing from them, one runs W. and passes near Riobamba; they call it the Rio de Chambo; after cutting through the Cordillera, its current turns E. and it becomes a large river; the Indians of the first province call it Corino, those of the second, Parosa. At 180 leagues from its source it unites with the great Rio de Orellana; there are extensive provinces on both sides of it but thinly settled. - 1112. Of the City of Sevilla del Oro in the Province of Macas.

The other river follows a straight course to the E., running near the city of Sevilla del Oro, and is named Opano. From this city its current turns S. and it traverses the Province of the Jibaros. The country is the richest in gold in all the Indies. The natives are cannibals and very warlike, and devastated the city of Logroño de los Caballeros, massacring the Spaniards and burning the churches. This was all caused by maladministration, negligence and injuries inflicted by higher officials on certain residents of this city.

There are numerous mentions in the historical record of the presence of gold at Logroño and Sevilla del Oro, but it is not clear if these are placer or hardrock occurrences. Juan de Alderete stated that in the first year almost 30,000 pesos of gold were produced at Logroño. A peso was 4.6g of “buen oro” (22.5 carat purity) (Lane, 1996). This meant that approximately 4,100 troy ounces were produced. A Caja Real or “Treasury Building” was established at Logroño to receive gold production so that the Quinto could be recorded (testimony, Diego Gonzalez Rengel, Quito 3rd September, 1591 in the presence of the President of Judges, AGI, QUITO 404). Juan Calvache, resident of Cuenca, who had travelled with Captain Bartolomé Perez on a punitive mission against the Jivaros stated:

(f.13v) They are [referring to the Jivaro] in lands that are very rich in gold. This witness in one week extracted 350 pesos of gold with six other men, and the witness said that this land was the richest in gold of all the Kingdoms of Peru. A lot of gold was extracted when there were work crews but this all came to an end when the Indians rebelled.”

This refers to an uprising in mid-1590 whereby 16 Spaniards were killed in Logroño de los Caballeros, and 40 were rescued (AGI, Legajo, QUITO 404, 127-3-15).

Also, Logroño was destroyed and rebuilt several times, and then when finally lost there were over time 30 unsuccessful attempts to recover it (AGI QUITO 143, N.20, Memorial Juan Bautista Sanchez de Orellana about the conquest of Logroño 29-02-1720) from which we can deduce it was considered worth the effort.

The historical record mentions the destruction of Logrono in 1578 and having been rebuilt in 1590. Vazquez de Espinosa says (writing in 1628) it was destroyed “30 years before” and an unreliable book from 1790 says it was destroyed in 1599. What is clear is that there is a total absence of mention of Logroño in any archival manuscript after 1605, other than to talk about its loss. It vanishes from maps after about 1650, and thereafter only appears over a hundred years later as the conjectured site of “ruins”.

It appears that gradually Sevilla del Oro was abandoned and then finally moved and the population employed in agriculture.

Two items are included below, for sake of completeness, and to once again illustrate that these were real places and not mythology, occupied and defended by real people, and sites of human tragedy. They also state that soldiers were sent to Santiago de los Montañas and Sevilla del Oro for aid to Logroño, and these must presumably have been the closest settlements.

Letter from the Royal Audience of Quito to their Majesty, 1579. (AGI/5, Quito 8, 6 ft)

Taylor –Landazuri: The Conquest of the Jibaro Region, 1550-1650, p. 108-9

“…The day after a group of people rebelled against us from one of the governorates of Juan de Salinas, these people called Gibaros and the city called Logroño; the rebellion took place as two Mestizos called all the aborigines and made them rebel coming after many Spanish settlements, killing 17 then and 3 more another day. Afterwards they intended to come to the aforementioned city and it must have been God who wanted to save the people of Logroño more for a miracle than the natural order; since we were notified in advance, we were prepared with large amounts of gun powder and lead and of people which is how we came to aid them. Some soldiers left afterwards with their respective leaders to destroy the attackers and because they had to cross a very mighty river, a raft of seven people was lost and another arrived with three less soldiers who were killed by Mestizos; the rest returned back to the city but were not able to cross through, and the two that were able to cross were killed offensively by Mestizos, who killed them as tokens of cruelty so that they could be recognized by the natives.”

AGI Patronage 126, R. 14. Merits and Services: Alonso Velásquez de Gavilanes: Chiapico etc. 1582

Proof of Services; Alonso de Velásquez Gavilanes, resident and mayor of Sevilla del Oro. Sevilla del Oro, April 19, 1582:

Witness Declaration: Francisco Machacón, mayor and neighbour of Sevilla del Oro:

“(doc.1, im.18) (…)This witness knows that a few days after mayor Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes passed through Spain to these parts of Peru, he started a journey and pacification of the Indians of the provinces of Chapico, Guano and Guayano. At his expense and mission he populated the city of Sevilla del Oro, in which captain Joseph de Villamar Maldonado entered the journey, (…) and the witness knew that it was in the city of Cuenca that they were preparing people and things that were necessary for the journey. Alonso de Gavilanes brought Francisco de Rojas to the journey with him, and had prepared the weapons and things necessary for the journey (…)

This witness knows that mayor Alonso Velásquez de Gavilanes served Your Majesty in the conquests and pacifications of the Indians of the provinces, until Jhoan de Salinas Loyola sent him with captain Bernardo de Loyola, to conquer and pacify the Indians of the provinces of Jívaros, Paringues and Aquiones. The witness knows that after three or four years the provinces of Jívaros were pacified and populated in Your Majesty’s name, and the city was called Logroño. Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes returned to the city of (Sevilla del Oro), where he was mayor, and in the city of Logroño he was supervisor of Your Majesty’s Real Hacienda (im.21) and he also became lieutenant and attorney of Sevilla del Oro; these responsibilities were given to him because he was a man of principal and honor (…)

This witness said that the soldiers of Palenque had a lot of work. They had to transport and cut the wood pile themselves. They did this in order to survive as they were very few waiting to be rescued (…) also (im.22) that some soldiers went down the river looking for help; three soldiers rafted to the city of Santiago, from where they were rescued. The witness believes that Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes was one of those who were able to escape to the city of Logroño where one can extract gold, and increase the “reales quintos” [King’s Fifth] of His Majesty.

The witness knows that the city has moved from where it was before, and he knows this because he heard it from residents of the city of Logroño, which at the time was above the Yndangoça River that the Spaniards called Ebro. He also knows that they removed the Indians from the provinces of Paringues and from the city of Logroño, who killed the seven Spaniards, and those from other nations who were capturing the Spaniards for their service. The witness knows this for a fact because he saw it with his own eyes, as he was one of the ones sent from the city of Sevilla del Oro to save the city of Logroño and to punish the criminals. He there heard that Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes, had left the city because of what happened with a few friends and they went to the province of Aximbaca where two of the people wanted to kill them, for being people of the belligerent provinces, their names were Juan Arias and Correa, soldiers of that journey. They wanted to kill mayor Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes and his accompanying soldiers with special weapons used by the people of the provinces of Aximbaca and Curahuangoça and Capiçango, which are countries where one cannot conquer Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes and his soldiers without a lot of work and risk of life. Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes went to the city of Logroño in the company of captain Juan Zapata, lieutenant governor, and very few soldiers. Also, the witness heard that they all returned to captain Bernardo de Loyola’s house, who had been outside of the provinces, and they could not stop themselves from guarding the city which was a lot of work because they were so few, nor could they stop the surveillance because the provinces were carrying out the punishments for the death of the 7 Spaniards (…)

(…) This witness knows from the experience that he had, and because he was imprisoned in the province of Paringues (…), due to the land having been so rough and mountainous and there being a lack of food, everyone had to work very hard (im.24). Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes, always had to carry his weapons on his back through the dangerous paths and ambushes (…), (and) he was forced many times to travel along dangerous paths, swimming across the rivers with weapons, also he had to cross very dangerous bridges which they say was normal in that area. During the times of war they were very dangerous because there were no Indians maintaining them. The witness also said that it was very dangerous and risky because of the rivers below were so big, and mighty. If someone was to fall in they would not escape without a miracle, and the rivers in those provinces were notorious for drowning Spaniards (…)

This witness said that Alonso Velázquez de Gavilanes came out of the provinces very sick. He came to this city after three or four months, without color and unhealthy (…), because during the conquest they lacked meat and corn, and they didn’t even have the roots that the Indians would eat. They went a very long time without eating (im.25), and they survived on eating grass alone (…)”

Fray Antonio José Prieto, a Franciscan missionary, is alleged to have discovered the ruins of Logroño in 1816, with José María Suero, Commander, a group of soldiers, and Indians from the settlement of Sigsig near Cuenca. Prieto claimed to have found stone foundations of buildings, a central plaza, and the remains of several walls and roads at the confluence of the Rio Bomboisa and Rio Sangurima. (AGI LEGAJO, QUITO 404, 127-2-15; AGI MISCELLANEOUS 4 A, 1816, R.2; AGI D.4.STATE 74, N. 50. Letter from the Marquis de la Concorde, 24- 07- 1817.) Prieto, Suero and various other dignitaries from the city of Cuenca who had financed the venture requested various lucrative postings and pensions from the Crown as a reward for the discovery but perhaps significantly none requested any part of any future gold mining. Francisco Requena, ex-Governor of Mainas, expressed doubts about the discovery as early as 1816 since he was familiar with the geography. (Audiencia y del Consejo de Indias, 2ª. Sala del Consejo del 14 de enero de 1820).

In any case any hopes to resurrect any lost mines were overtaken by events in Europe. Napoleon Bonaparte and his armies overthrew the Spanish Crown and shortly thereafter the South American colonies began to proclaim independence. The city of Guayaquil was the first in Ecuador (1820), and Quito in (1822). Soon thereafter an end to Spanish rule was declared and the Spaniards expelled from Ecuador. The Prieto sites, now known as “El Remanso” and “Buenos Aires” are near the town of Gualaquiza, in the northern part of the Cordillera del Condor. They are believed by archaeologists to be pre-Columbian.

In 2008 a book was published in Madrid by Dr. Carmen Martinez Martin; Una ciudad perdida en la Amazonia: Logroño de los Caballeros. (A lost city in the Amazon: Logroño de los Caballeros). In this 199 page book which is predominantly ethno- and historical background material, the Prieto site is declared to be the ancient city of Logroño. There is no mention or discussion of archeological studies carried out over the last 50 years and Martinez seems to be unaware of them. The two sites of ruins found by Prieto are on active farms on cleared land where cattle are presently being grazed. Though minor gold is known from streams in the vicinity of Gualaquiza and Bomboiza nearby, there are no active or abandoned mine sites.